Po 47 latach i 25 miliardach mil na pokładzie znajduje się eksperyment naukowy dotyczący plazmy[{” attribute=”” tabindex=”0″ role=”link”>NASA’s Voyager 2 spacecraft has been turned off.

NASA’s twin Voyager spacecraft were originally designed for a four-year mission to explore Jupiter and Saturn. Nearly 50 years and 15 billion miles later, they have far surpassed this goal, venturing past the outer planets, busting out of our heliosphere, and into interstellar space. These probes are now the most distant human-made objects, moving farther from Earth every day.

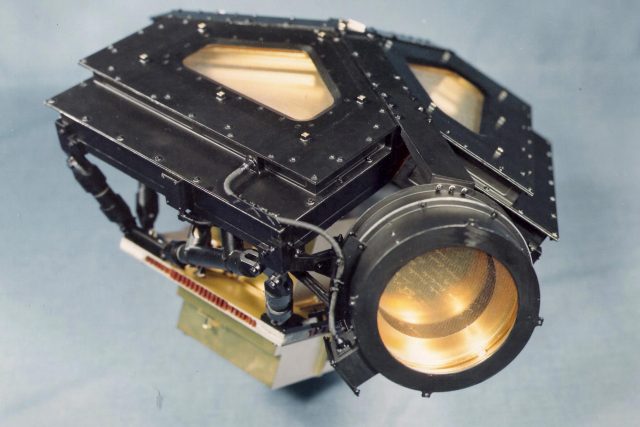

Throughout their extraordinary journey, the Voyagers made groundbreaking observations of all four giant outer planets and their moons, using just a few instruments. Among these was MIT’s Plasma Science Experiment — a pair of identical plasma sensors created in the 1970s by MIT scientists and engineers in Building 37. These instruments enabled first-of-their-kind measurements that expanded our understanding of the solar system.

The Plasma Science Experiment (also known as the Plasma Spectrometer, or PLS for short) measured charged particles in planetary magnetospheres, the solar wind, and the interstellar medium, the material between stars. Since launching on the Voyager 2 spacecraft in 1977, the PLS has revealed new phenomena near all the outer planets and in the solar wind across the solar system. The experiment played a crucial role in confirming the moment when Voyager 2 crossed the heliosphere and moved outside of the sun’s regime, into interstellar space.

Now, to conserve the little power left on Voyager 2 and prolong the mission’s life, the Voyager scientists and engineers decided to shut off MIT’s Plasma Science Experiment. It’s the first in a line of science instruments that will progressively blink off over the coming years. On September 26, the Voyager 2 PLS sent its last communication from 12.7 billion miles away, before it received the command to shut down.

MIT News spoke with John Belcher, the Class of 1922 Professor of Physics at MIT, who was a member of the original team that designed and built the plasma spectrometers, and John Richardson, principal research scientist at MIT’s Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research, who is the experiment’s principal investigator. Both Belcher and Richardson offered their reflections on the retirement of this interstellar piece of MIT history.

Q: Looking back at the experiment’s contributions, what are the greatest hits, in terms of what MIT’s Plasma Spectrometer has revealed about the solar system and interstellar space?

Richardson: A key PLS finding at Jupiter was the discovery of the Io torus, a plasma donut surrounding Jupiter, formed from sulphur and oxygen from Io’s volcanos (which were discovered in Voyager images). At Saturn, PLS found a magnetosphere full of water and oxygen that had been knocked off of Saturn’s icy moons. At Uranus and Neptune, the tilt of the magnetic fields led to PLS seeing smaller density features, with Uranus’ plasma disappearing near the planet. Another key PLS observation was of the termination shock, which was the first observation of the plasma at the largest shock in the solar system, where the solar wind stopped being supersonic. This boundary had a huge drop in speed and an increase in the density and temperature of the solar wind. And finally, PLS documented Voyager 2’s crossing of the heliopause by detecting a stopping of outward-flowing plasma. This signaled the end of the solar wind and the beginning of the local interstellar medium (LISM). Although not designed to measure the LISM, PLS constantly measured the interstellar plasma currents beyond the heliosphere. It is very sad to lose this instrument and data!

Belcher: It is important to emphasize that PLS was the result of decades of development by MIT Professor Herbert Bridge (1919-1995) and Alan Lazarus (1931-2014). The first version of the instrument they designed was flown on Explorer 10 in 1961. And the most recent version is flying on the Solar Probe, which is collecting measurements very close to the sun to understand the origins of solar wind. Bridge was the principal investigator for plasma probes on spacecraft which visited the sun and every major planetary body in the solar system.

Q: During their tenure aboard the Voyager probes, how did the plasma sensors do their job over the last 47 years?

Richardson: There were four Faraday cup detectors designed by Herb Bridge that measured currents from ions and electrons that entered the detectors. By measuring these particles at different energies, we could find the plasma velocity, density, and temperature in the solar wind and in the four planetary magnetospheres Voyager encountered. Voyager data were (and are still) sent to Earth every day and received by NASA’s deep space network of antennae. Keeping two 1970s-era spacecraft going for 47 years and counting has been an amazing feat of JPL engineering prowess — you can google the most recent rescue when Voyager 1 lost some memory in November of 2023 and stopped sending data. JPL figured out the problem and was able to reprogram the flight data system from 15 billion miles away, and all is back to normal now. Shutting down PLS involves sending a command that will get to Voyager 2 about 19 hours later, providing the rest of the spacecraft enough power to continue.

Q: Once the plasma sensors have shut down, how much more could Voyager do, and how far might it still go?

Richardson: Voyager will still measure the galactic cosmic rays, magnetic fields, and plasma waves. The available power decreases about 4 watts per year as the plutonium which powers them decays. We hope to keep some of the instruments running until the mid-2030s, but that will be a challenge as power levels decrease.

Belcher: Nick Oberg at the Kapteyn Astronomical Institute in the Netherlands has made an exhaustive study of the future of the spacecraft, using data from the European Space Agency’s spacecraft Gaia. In about 30,000 years, the spacecraft will reach the distance to the nearest stars. Because space is so vast, there is zero chance that the spacecraft will collide directly with a star in the lifetime of the universe. However, the spacecraft’s surface will erode by microcollisions with vast clouds of interstellar dust, but this happens very slowly.

In Oberg’s estimate, the Golden Records [identical records that were placed aboard each probe, that contain selected sounds and images to represent life on Earth] prawdopodobnie przetrwają ponad 5 miliardów lat. Po tych 5 miliardach lat trudno jest przewidzieć sytuację, ponieważ w tym momencie Droga Mleczna zderzy się ze swoją masywną sąsiadką, galaktyką Andromedy. Podczas tej kolizji istnieje szansa jedna na pięć, że statek kosmiczny zostanie wrzucony do ośrodka międzygalaktycznego, gdzie jest mało pyłu i niewielkie wietrzenie. W takim przypadku możliwe jest, że statek kosmiczny przetrwa biliony lat. Bilion lat to około 100 razy więcej niż obecny wiek Wszechświata. Ziemia przestaje istnieć za około 6 miliardów lat, kiedy Słońce wchodzi w fazę czerwonego olbrzyma i pochłania ją.

W „biednej” wersji Złotej Płyty Robert Butler, główny inżynier Instrumentu Plazmowego, wpisał nazwiska inżynierów i naukowców z MIT, którzy pracowali nad statkiem kosmicznym, na płycie kolektora skierowanego z boku kubka. Rodzinnym stanem Butlera było New Hampshire, a na szczycie listy nazwisk umieścił motto stanu: „Żyj wolny lub giń”. Dzięki Butlerowi, choć New Hampshire nie przetrwa bilionów lat, jego motto stanu może. Część zapasowa instrumentu PLS jest obecnie eksponowana w Muzeum MIT, gdzie można zobaczyć tekst wiadomości Butlera, spoglądając w boczny czujnik.