Prawie 40 lat po podróży Voyagera 2[{” attribute=”” tabindex=”0″ role=”link”>NASA plans to revisit Uranus to explore its moons for hidden liquid water oceans, using a new computer model.

This model analyzes the moons’ rotational wobbles to infer the presence and size of subsurface oceans. The findings could significantly influence our understanding of life’s potential in the galaxy, as ice giants and their moons might be prevalent habitats.

Voyager’s Historic Encounter and Future Plans

In 1986, NASA’s Voyager 2 flew past Uranus, capturing grainy images of its large, ice-covered moons. Nearly 40 years later, NASA is planning a new mission to the distant planet, this time equipped to determine if those icy moons conceal liquid water oceans beneath their surfaces.

Though the mission is still in its early planning stages, researchers at the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics (UTIG) are already developing a computer model designed to detect these hidden oceans using only the spacecraft’s cameras.

This research is crucial because scientists are unsure which techniques will be most effective for finding oceans on Uranus. Confirming the presence of liquid water is a priority, as it is a fundamental ingredient for life.

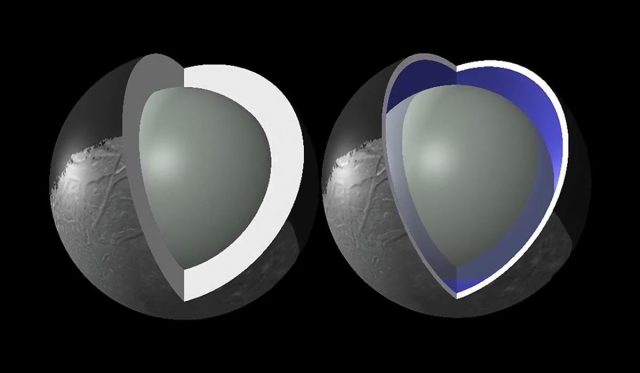

The new computer model works by analyzing small oscillations — or wobbles — in the way a moon spins as it orbits its parent planet. From there it can calculate how much water, ice and rock there is inside. Less wobble means a moon is mostly solid, while a large wobble means the icy surface is floating on a liquid water ocean. When combined with gravity data, the model computes the ocean’s depth as well as the thickness of the overlying ice.

Understanding Ice Giants and Life Potential

Uranus, along with Neptune, is in a class of planets called ice giants. Astronomers have detected more ice giant-sized bodies outside of our solar system than any other kind of exoplanet. If Uranus’s moons are found to have interior oceans, that could mean there are vast numbers of potentially life-harboring worlds throughout the galaxy, said UTIG planetary scientist Doug Hemingway, who developed the model.

“Discovering liquid water oceans inside the moons of Uranus would transform our thinking about the range of possibilities for where life could exist,” he said.

The UTIG research, which was published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, will help mission scientists and engineers improve their chances of detecting oceans. UTIG is a research unit of the Jackson School of Geosciences at The University of Texas at Austin.

Mechanics of Moons’ Oscillations

All large moons in the solar system, including Uranus’s, are tidally locked. This means that gravity has matched their spin so that the same side always faces their parent planet while they orbit. This doesn’t mean their spin is completely fixed, however, and all tidally locked moons oscillate back and forth as they orbit. Determining the extent of the wobbles will be key to knowing if Uranus’s moons contain oceans, and if so, how large they might be.

Moons with a liquid water ocean sloshing about on the inside will wobble more than those that are solid all the way through. However, even the largest oceans will generate only a slight wobble: A moon’s rotation might deviate only a few hundred feet as it travels through its orbit.

That’s still enough for passing spacecraft to detect. In fact, the technique was previously used to confirm that Saturn’s moon Enceladus has an interior global ocean.

Animacja pokazująca, jak księżyc Urana, Ariel, może kołysać się w wewnętrznym oceanie (po prawej), w porównaniu z tym, jak jest stały aż do jądra (po lewej). Przedstawione wahania są przesadzone. Model komputerowy opracowany w ramach projektu UTIG może obliczyć grubość oceanu i pokrywającego go lodu (warstwa o jaśniejszym kolorze), analizując wahania i łącząc je z innymi pomiarami. Źródło: Doug Hemingway

Rozszerzanie technik wykrywania oceanów

Aby dowiedzieć się, czy ta sama technika sprawdzi się w przypadku Urana, Hemingway przeprowadził obliczenia teoretyczne dla pięciu jego księżyców i przedstawił szereg prawdopodobnych scenariuszy. Na przykład, jeśli księżyc Urana, Ariel, zatacza się na odległość 90 metrów, wówczas prawdopodobnie będzie miał ocean głęboki na 300 km otoczony skorupą lodową o grubości 30 km.

Wykrywanie mniejszych oceanów będzie oznaczać, że statek kosmiczny będzie musiał zbliżyć się lub wyposażyć w wyjątkowo mocne kamery. Jednak model daje projektantom misji suwak logarytmiczny, dzięki któremu wiedzą, co będzie działać, powiedziała profesor nadzwyczajna UTIG Research, Krista Soderlund.

„Może to stanowić różnicę między odkryciem oceanu a stwierdzeniem, że po przybyciu na miejsce nie mamy takich możliwości” – powiedział Soderlund, który nie był zaangażowany w obecne badania.

Soderlund współpracował z NASA nad koncepcjami misji na Urana. Jest także częścią zespołu naukowego NASA Europy Misja Clipper, która niedawno wystrzeliła i przenosi radarowy radar penetrujący lód opracowany przez UTIG.

Następnym krokiem, powiedział Hemingway, jest rozszerzenie modelu o pomiary wykonane innymi instrumentami, aby zobaczyć, jak poprawiają one obraz wnętrz księżyców.

Odniesienie: „Looking for Undersurface Oceans Within the Moons of Urana using Librations and Gravity” (Szukanie podpowierzchniowych oceanów w obrębie księżyców Urana przy użyciu libracji i grawitacji), DJ Hemingway i F. Nimmo, 15 września 2024 r., Listy z badań geofizycznych.

DOI: 10.1029/2024GL110409

Współautorem artykułu jest Francis Nimmo z Uniwersytetu Kalifornijskiego w Santa Cruz. Badania sfinansował UTIG.