Historyczne lądowanie Philae na komecie 67P w 2014 roku dostarczyło kluczowych danych na temat powierzchni komety i składu wewnętrznego, pomimo niepowodzeń technicznych.

Misja ujawniła cząsteczki organiczne i zmiany temperatury, oferując wgląd w starożytne materiały tworzące nasz Układ Słoneczny. To przełomowe osiągnięcie przygotowało grunt pod przyszłe misje badawcze do innych ciał komet i asteroid.

Historyczne przyłożenie

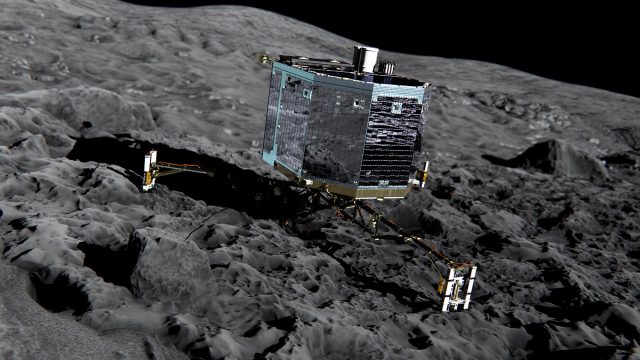

12 listopada 2014 r., po dziesięcioletniej podróży obejmującej Układ Słoneczny i ponad 500 milionów kilometrów, lądownik Rosetty Philae przeszedł do historii, stając się pierwszym statkiem kosmicznym, który wylądował na komecie. jako[{” attribute=”” tabindex=”0″ role=”link”>European Space Agency (ESA) marks the tenth anniversary of this groundbreaking achievement, they honor Philae’s remarkable contributions to space exploration at Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko.

Choosing the Landing Site

When Rosetta arrived at Comet 67P on August 6, 2014, the mission team immediately began the race to select a suitable landing site for Philae. The site had to strike a careful balance between safety and scientific potential.

Using high-resolution images captured by Rosetta, scientists meticulously analyzed and debated various candidate sites. After weeks of deliberation, they chose a smooth-looking region on the smaller of the comet’s two lobes. This location was named Agilkia, and it offered the best combination of stability and opportunities for groundbreaking science.

Intense preparations followed, but the night before landing, a problem was identified: Philae’s active descent system, which would provide a downward thrust to prevent rebound at touchdown, could not be activated. Philae would have to rely on harpoons and ice screws in its three feet to fix it to the surface.

Nonetheless, the green light was given and after separating from Rosetta, Philae began its seven-hour descent to the surface of the comet. During the descent, Philae began ‘sensing’ the environment around the comet, taking stunning imagery as the first landing site came into view.

First Contact With a Comet

Philae’s touchdown at Agilkia was spot-on. The sensors on Philae’s feet felt the touchdown vibrations, generating the first recording of contact between a human-made object and a comet. But it soon became clear that Philae’s harpoons hadn’t fired and it had taken flight again.

In the end, Philae made contact with the surface four times. Thanks to an automatic sequence that was triggered by the first touchdown signal, Philae’s instruments were operating while in flight, collecting unique data that would later yield important results. It was also an unexpected bonus that data were collected at more than one location, providing the first direct measurements of surface characteristics and allowing comparisons between the touchdown sites.

For example, Philae ‘felt’ the difference in surface texture and hardness as it bounced from one site to another. At the first landing site, it detected a soft layer several centimeters thick, milliseconds later encountering a much harder layer.

After colliding with a cliff, Philae scraped through its second touchdown site, providing the first in situ measurement of the softness of the icy-dust interior of a boulder on a comet. The simple action of Philae ’stamping’ an imprint in billions-of-years-old ice revealed the boulder to be fluffier than froth on a cappuccino, equivalent to a porosity of about 75%.

APXS: Alpha Proton X-ray Spectrometer (studying the chemical composition of the landing site and its potential alteration during the comet’s approach to the Sun)

CIVA: Comet Nucleus Infrared and Visible Analyser (six cameras to take panoramic pictures of the comet surface)

CONSERT: COmet Nucleus Sounding Experiment by Radiowave Transmission (studying the internal structure of the comet nucleus with Rosetta orbiter)

COSAC: The COmetary SAmpling and Composition experiment (detecting and identifying complex organic molecules)

PTOLEMY: Using MODULUS protocol (Methods Of Determining and Understanding Light elements from Unequivocal Stable isotope compositions) to understand the geochemistry of light elements, such as hydrogen, carbon, nitrogen and oxygen.

MUPUS: MUlti-PUrpose Sensors for Surface and Sub-Surface Science (studying the properties of the comet surface and immediate sub-surface)

ROLIS: Rosetta Lander Imaging System (providing the first close-up images of the landing site)

ROMAP: Rosetta Lander Magnetometer and Plasma Monitor (studying the magnetic field and plasma environment of the comet)

SD2: Sampling, drilling and distribution subsystem (drilling up to 23 cm depth and delivering material to onboard instruments for analysis)

SESAME: Surface Electric Sounding and Acoustic Monitoring Experiment (probing the mechanical and electrical parameters of the comet)

Credit: ESA/ATG medialab

The Scientific Harvest

Philae then ‘hopped’ about 30 meters to the final touchdown site, named Abydos, where its CIVA cameras provided the first image of a human-made object touching a 4.6 billion year old Solar System relic. The exact location on the comet would remain hidden from view for almost two years.

In this location, Philae’s MUPUS hammer penetrated a soft layer before encountering an unexpectedly hard surface a few centimeters below the surface. Philae ‘listened’ to the hammering with its feet, recording the vibrations that passed through the comet. This was the first time since the Apollo 17 mission to the Moon in 1972 that active seismic measurements were conducted on a celestial body.

MUPUS also carried a thermal sensor, which measured the local changes in temperature from about -180ºC to 145ºC, in sync with the comet’s 12.4 hour day – the first time the temperature cycle of a comet had been measured at its surface.

Meanwhile the CONSERT experiment, which passed radio waves between Rosetta and Philae through the comet in the first cometary sounding experiment, revealed the interior of the comet to be a very loosely compacted mixture of dust and ice, with a high porosity of 75–85%.

In-Flight Discoveries

During the bouncing, Philae’s COSAC and Ptolemy instruments ‘sniffed’ the comet’s gas and dust, important tracers of the raw materials present in the early Solar System. COSAC revealed a suite of 16 organic compounds comprising numerous carbon and nitrogen-rich compounds, including methyl isocyanate, acetone, propionaldehyde, and acetamide that had never before been detected in comets. The complex molecules detected by both COSAC and Ptolemy play a key role in the synthesis of the ingredients needed for life.

Philae’s bouncing also allowed it to measure the magnetic field at different heights above the surface, showing the comet is remarkably non-magnetic. Detecting the magnetic field of comets has proven difficult in previous missions, which have typically flown past at high speeds, relatively far from comet nuclei. It took the proximity of Rosetta’s orbit around the comet and the measurements made much closer to and at the surface by Philae, to provide the first detailed investigation of the magnetic properties of a comet nucleus.

In the end some 80% of Philae’s planned science sequence was completed in the 64 hours following separation from Rosetta and before the lander fell into hibernation.

While Philae hibernated, Rosetta continued returning an unprecedented wealth of information from the comet as it orbited around the Sun, watching the comet’s activity reach a peak and then slowly subside again. Philae would be heard from briefly in June–July 2015 but could not be reactivated. Then, as Rosetta’s mission was drawing to its planned end with its own daring descent to the surface at a site named Sais, Philae’s final landing site was revealed in orbiter imagery, a final twist in what had become one of the greatest stories of space exploration.

Torowanie drogi dla przyszłych misji

ESA może poszczycić się imponującym dziedzictwem w badaniach małych ciał, a podwójny akt Rosetta-Philae zainspirował kolejną generację tropicieli komet i asteroid.

ESA Giotto misja przelotu obok komety Halleya w 1986 r. była pierwszą misją, podczas której wykonano zdjęcia powierzchni komety. Misja Rosetta była naturalnym kolejnym krokiem, gdyż jako pierwsza okrążyła kometę i umieściła na jej powierzchni lądownik. Rosetta była także pierwszą osobą, która podążała za kometą wokół Słońca, monitorując jej aktywność w trakcie największego zbliżenia się do Słońca.

Rosetta toruje drogę nadchodzącej misji Comet Interceptor, która w przeciwieństwie do swoich poprzedników po raz pierwszy zbada kometę odwiedzającą nasz Układ Słoneczny. W związku z tym kometa będzie zawierać materię, która została poddana minimalnej obróbce, co zapewni „czystszy” wygląd nieskazitelnej materii z początków Układu Słonecznego, zanim została wyrzeźbiona przez ciepło Słońca. Misja będzie składać się z głównej sondy i dwóch sond, które zapewnią kometę pod różnymi kątami.

ESA odwiedza także asteroidy, a jej flagowy „obrońca planet” Hera udaje się na badanie Dimorphos NASAeksperyment uderzeniowy mający na celu zmianę jego trajektorii, będący testem na wielką skalę technik obrony planetarnej. Schemat orbity Hery został zapożyczony bezpośrednio od Rosetty, a dwa mniejsze satelity misji wyposażone są w radary i przyrządy do pomiaru pyłu oparte na tych zaprojektowanych dla Rosetty.

Tymczasem Ramzes będzie towarzyszyć asteroidzie Apophis podczas wyjątkowo bliskiego przelotu obok Ziemi w 2029 r. I będzie wielkości walizki M-Argo będzie najmniejszym statkiem kosmicznym, który wykona własną niezależną misję w przestrzeni kosmicznej, kiedy pod koniec tej dekady spotka się z małą asteroidą bliską Ziemi.

Dziedzictwo Rosetty i Philae żyje także w sercach i umysłach ludzi, co zostało ujawnione w naszej książce nowa wystawa internetowa świętując tę wyjątkowo inspirującą misję.

Rosetta była misją ESA, w którą zaangażowały się jej państwa członkowskie i NASA. Oprogramowanie Philae dostarczyło konsorcjum pod przewodnictwem DLR, MPS, CNES i ASI.