Niedawne odkrycia ujawniają, że wybuchy wolno pulsujących fal radiowych pochodzą z układu podwójnego gwiazd składającego się z czerwonego karła i gwiazdy[{” attribute=”” tabindex=”0″ role=”link”>white dwarf.

These findings challenge current pulsar theories and indicate a wider variety of stellar systems may emit similar signals.

Radio Wave Mysteries

Since 2022, astronomers have been puzzled by bursts of intense radio waves from deep space that slowly repeat at regular intervals. These signals, unlike anything seen before, defy conventional understanding of how such cosmic phenomena work.

For the first time, new research has traced one of these mysterious signals back to its source: a common, lightweight star called a red dwarf. It appears to be in a binary orbit with a white dwarf — the dense core left behind when a star similar to our Sun dies in a dramatic explosion.

Discovery of a New Cosmic Phenomenon

In 2022, our team made a remarkable discovery: periodic radio pulses from space that repeated every 18 minutes. The bursts were incredibly bright, outshining anything nearby. After three months of flashing, they vanished without a trace.

We know that some repeating radio signals come from neutron stars known as radio pulsars. These stars spin rapidly, often rotating once per second or even faster, sending out beams of radio waves like a lighthouse. However, based on what we currently understand, a pulsar spinning as slowly as once every 18 minutes shouldn’t be able to produce radio waves at all.

This unexpected finding suggested we might be dealing with an entirely new type of astronomical phenomenon — or that our understanding of how pulsars emit radio waves needs to be reconsidered.

More slowly blinking radio sources have been discovered since then. There are now about ten known “long-period radio transients.”

However, just finding more hasn’t been enough to solve the mystery.

Searching the Outskirts of the Galaxy

Until now, every one of these sources has been found deep in the heart of the Milky Way.

This makes it very hard to figure out what kind of star or object produces the radio waves, because there are thousands of stars in a small area. Any one of them could be responsible for the signal, or none of them.

So, we started a campaign to scan the skies with the Murchison Widefield Array radio telescope in Western Australia, which can observe 1,000 square degrees of the sky every minute. An undergraduate student at Curtin University, Csanád Horváth, processed data covering half of the sky, looking for these elusive signals in more sparsely populated regions of the Milky Way.

And sure enough, we found a new source! Dubbed GLEAM-X J0704-37, it produces minute-long pulses of radio waves, just like other long-period radio transients. However, these pulses repeat only once every 2.9 hours, making it the slowest long-period radio transient found so far.

Pinpointing the Source of Radio Waves

We performed follow-up observations with the MeerKAT telescope in South Africa, the most sensitive radio telescope in the southern hemisphere. These pinpointed the location of the radio waves precisely: they were coming from a red dwarf star. These stars are incredibly common, making up 70% of the stars in the Milky Way, but they are so faint that not a single one is visible to the naked eye.

Combining historical observations from the Murchison Widefield Array and new MeerKAT monitoring data, we found that the pulses arrive a little earlier and a little later in a repeating pattern. This probably indicates that the radio emitter isn’t the red dwarf itself, but rather an unseen object in a binary orbit with it.

Based on previous studies of the evolution of stars, we think this invisible radio emitter is most likely to be a white dwarf, which is the final endpoint of small to medium-sized stars like our own Sun. If it were a neutron star or a black hole, the explosion that created it would have been so large it should have disrupted the orbit.

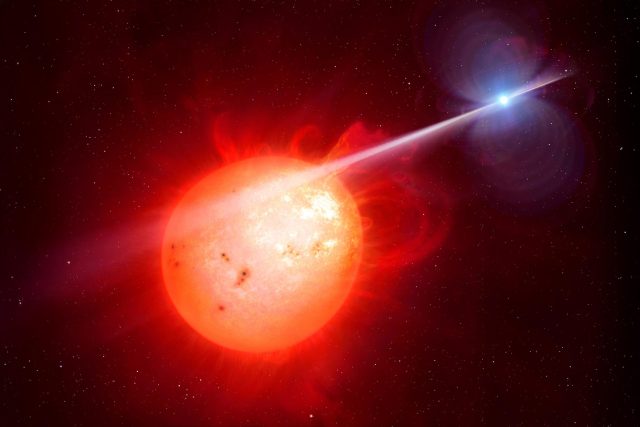

Artystyczna wizja systemu AR Sco: układ podwójny czerwony i biały karzeł, które oddziałują ze sobą, wytwarzając emisję radiową.

Rola systemu binarnego w produkcji fal radiowych

W jaki sposób czerwony i biały karzeł generują sygnał radiowy?

Czerwony karzeł prawdopodobnie wytwarza wiatr gwiazdowy złożony z naładowanych cząstek, podobnie jak robi to nasze Słońce. Kiedy wiatr uderza w pole magnetyczne białego karła, ulega przyspieszeniu, wytwarzając fale radiowe.

Może to być podobne do interakcji słonecznego wiatru gwiazdowego z ziemskim polem magnetycznym, tworząc piękne obrazy zorza polarnaa także fale radiowe o niskiej częstotliwości.

Kontynuacja poszukiwania odpowiedzi

Znamy już kilka takich systemów, jak np AR Scorpiigdzie różnice w jasności czerwonego karła oznaczają, że towarzyszący mu biały karzeł uderza w niego potężną wiązką fal radiowych co dwie minuty. Żaden z tych systemów nie jest tak jasny ani tak powolny jak długookresowe stany przejściowe radiowe, ale być może, gdy znajdziemy więcej przykładów, opracujemy ujednolicony model fizyczny, który wyjaśni je wszystkie.

Z drugiej strony może tak być wiele różny rodzaje systemu, który może wytwarzać długotrwałe pulsacje radiowe.

Tak czy inaczej, nauczyliśmy się, jak można oczekiwać nieoczekiwanego i będziemy nadal skanować niebo, aby rozwiązać tę kosmiczną tajemnicę.

Napisane przez Natashę Hurley-Walker, radioastronom z Curtin University.

Na podstawie artykułu pierwotnie opublikowanego w Rozmowa.![]()